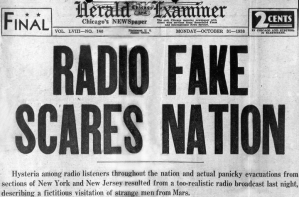

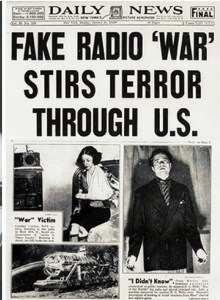

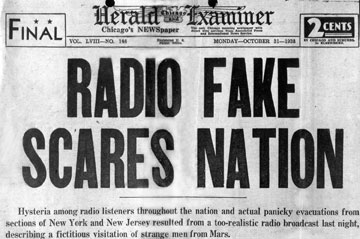

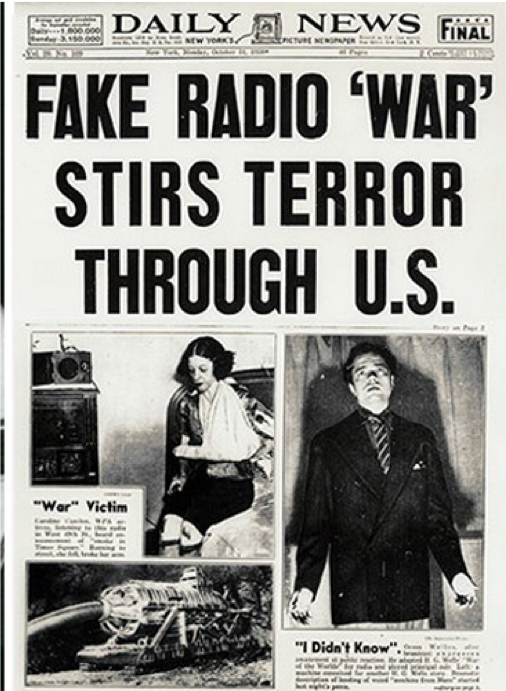

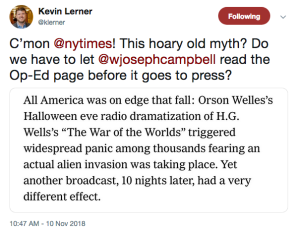

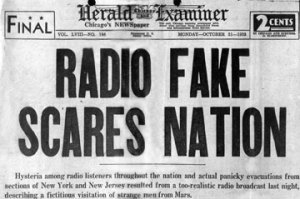

Eighty-two years ago, the front pages of American newspapers told of panic and hysteria which, they said, had swept the country the night before, during, and immediately after a radio dramatization of The War of the Worlds.

The program starred and was directed by 23-year-old Orson Welles who made clever use of simulated news bulletins to tell of waves of attack ing Martians wielding deadly heat rays. So vivid and frightening was the program that tens of thousands of Americans were convulsed in panic and driven to hysteria.

ing Martians wielding deadly heat rays. So vivid and frightening was the program that tens of thousands of Americans were convulsed in panic and driven to hysteria.

Or so the newspapers said on October 31, 1938.

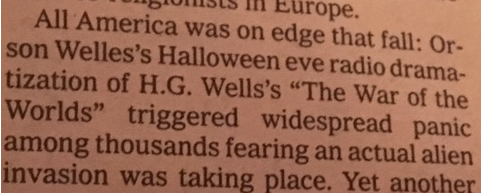

“For an hour, hysterical pandemonium gripped the Nation’s Capital and the Nation itself,” declared the Washington Post, while offering few specifics to support the dramatic claim.

“Thousands of persons in New Jersey and the metropolitan area, as well as all over the nation, were pitched into mass hysteria … by the broadcast,” the New York Herald Tribune asserted. It, too, offered little supporting evidence.

“Hysteria among radio listeners through the nation … resulted from a too realistic radio program … describing a fictitious and devastating visitation of strange men from Mars,” reported the San Francisco Chronicle.

And so it went.

As I described in my media-mythbusting book, Getting It Wrong, reports of widespread panic and hysteria were wildly exaggerated “and did not occur on anything approaching a nationwide scale.”

Had Americans been convulsed in panic and hysteria that night, the resulting turmoil and mayhem surely would have resulted in deaths, including suicides, and in serious injuries. But nothing of the sort was conclusively linked to the show.

The overheated press accounts were almost entirely anecdotal — and driven by an eagerness to question the reliability and legitimacy of radio, then an upstart rival medium.

There was no nationwide panic that long ago night before Halloween and the day-after coverage was an episode of collective misreporting that contributed to the rise of a tenacious media myth.

Eighty-two years later, much of mainstream corporate news media is indulging in another, even more consequential episode of misconduct that’s defined not by overheated misreporting but by willful blindness on an extraordinary scale.

Corporate media, with few exceptions on the political right, have ignored and declined to pursue allegations of international influence-peddling by the son of Democratic presidential nominee, Joe Biden, so as to shield the flawed and feeble candidate from scrutiny and help him defeat the incumbent they so profoundly loathe.

Their contempt for President Donald Trump runs deep. Corporate media obviously recognize they cannot investigate and publish critical reporting — they cannot do searching journalism — about Biden so close to the November election without jeopardizing his candidacy and boosting Trump’s chances of reelection.

This neglect by corporate media represents an abdication of fundamental journalistic values of detachment, and impartiality. A defining ethos of American journalism that emerged during the second half of the Twentieth Century emphasized even-handed treatment of the news and an avoidance of overt, blatant partisanship.

This neglect by corporate media represents an abdication of fundamental journalistic values of detachment, and impartiality. A defining ethos of American journalism that emerged during the second half of the Twentieth Century emphasized even-handed treatment of the news and an avoidance of overt, blatant partisanship.

Rank-and-file journalists tended to regard politicians of both major parties with a mixture of suspicion and mild contempt. It was a kind of “fie on both houses” attitude. Running interference for a politician was considered more than a little unsavory.

Not so much anymore. Not in American corporate media, where an overt partisanship has become not only acceptable but unmistakable.

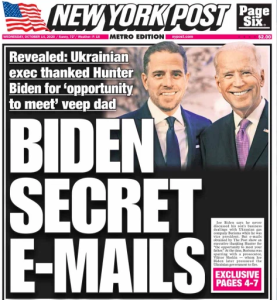

The suspicions about Biden stem from his son’s efforts to line up lucrative, pay-for-play business arrangements in Ukraine — supposedly without the knowledge of Joe Biden. Reporting in the New York Post in mid-October was based on emails that undercut Biden’s claim of ignorance about the son’s dealings. Notably, the Bidens have not disputed the authenticity of the emails. Nor have they substantively addressed the allegations.

Subsequent reports have suggested Biden’s secret financial involvement in his son’s attempts to arrange a lucrative deal with a Chinese energy company tied to the country’s communist government.

The narratives are detailed, with many dimensions and potential implications — all which make media scrutiny all the more urgent.

But the response largely has been to shun and ignore. Or to block or impede distribution, as Twitter and Facebook did with the New York Post’s mid-October report. Or to dismiss it as so much Russian disinformation. Or scoff that it’s just a distraction. That’s what National Public Radio claimed, in a remarkably obtuse statement by its public editor (or internal critic), Kelly McBride. “We don’t want to waste our time,” she wrote, ” … on stories that are just pure distractions.”

Matt Taibbi, who is perhaps the most searching critic these days of contemporary American media and their failings, noted recently that the “least curious people in the country right now appear to be the credentialed news media, a situation normally unique to tinpot authoritarian societies.”

The inclination to shield Biden may partly stem from the shifting business model for corporate news organizations. The model used to be largely advertising-based, which encouraged news organizations to seek wide audiences by offering what was passably impartial reporting.

With the decline of advertising revenues, the business model has moved toward a digital-subscriber base. As readers pay, they are prone to make clear their preferences, and the news report tilts to reflect their partisan expectations.

Evidence of the tilt was striking enough four years ago, when Liz Spayd, an advocate of even-handedness in reporting, was public editor at the New York Times. She lasted less than a year before the position was dissolved and she was let go.

Spayd, whom I favorably mention in my latest book, Lost in a Gallup: Polling Failure in U.S. Presidential Elections, hadn’t been on the job a month when she wrote this about the Times in July 2016:

“Imagine what would be missed by journalists who felt no pressing need to see the world through others’ eyes. Imagine the stories they might miss, like the groundswell of isolation that propelled a candidate like Donald Trump to his party’s nomination. Imagine a country where the greatest, most powerful newsroom in the free world was viewed not as a voice that speaks to all but as one that has taken sides.

“Or has that already happened?”

It no doubt had. And overt partisanship has become all the more evident in the past four years as the Times and other corporate media pursued such stories as Trump’s conspiring with Russia to steal the 2016 election. It was a bizarre, exaggerated tale that obsessed corporate media for three years before finally coming a cropper.

Corporate media may well protect Biden long enough for the gaffe-prone 77-year-old to gain the presidency. But the shameful exhibition of willful blindness may not end well for corporate media. Their abdication may leave them besmirched. And diminished.

More from Media Myth Alert:

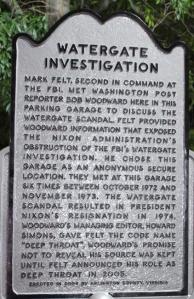

- Why Trump-Russia is hardly Nixon-Watergate

- Why Trump-Russia is still not Watergate redux

- Of Trump’s chances and Mark Twain’s ‘exaggerated’ quip

- Mythmaking in Moscow: Biden says WaPo brought down Nixon

- ‘War of the Worlds’ radio panic was overstated

- Halloween’s greatest media myth

- Why ‘War of the Worlds’ show didn’t panic America

- ‘Getting It Wrong’ goes on Q-and-A

“Fake news” has plenty of antecedents in mainstream media — several cases of which are examined in my mythbusting book,

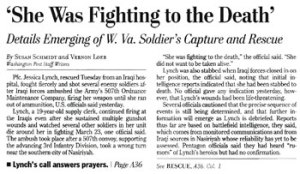

“Fake news” has plenty of antecedents in mainstream media — several cases of which are examined in my mythbusting book,  fiercely in the ambush of her unit during the early days of the Iraq War in 2003. Lynch, the

fiercely in the ambush of her unit during the early days of the Iraq War in 2003. Lynch, the