Much has been written already this year about 1968, a tumultuous and divisive time of war, civil protest, political upheaval, and bloodshed. It was, we’re told, a year that changed America, or even changed America forever.

It’s also true, if less hyperbolic, that 1968 can be considered a foundation year for media myths, signaling anew how understanding of the past can be warped by dubious tales and exaggerated interpretations.

At the Freedom Trash Can

Three prominent and tenacious media myths stem from 1968 — the presumptive “Cronkite Moment,” which is said to have dramatically altered views about the Vietnam War; the “secret plan” for ending that war, a plan on which Richard Nixon supposedly campaigned for the presidency; and the nuanced myth of bra-burning at the Miss America pageant in September 1968.

Not surprisingly, credulous references to those myths have appeared in recent news accounts and commentaries about the 50th anniversary of 1968.

Notable among the references have been those about the “Cronkite Moment” of February 27, 1968. That was when CBS News anchorman Walter Cronkite offered a pessimistic assessment of the war in Vietnam, asserting that the U.S. military was “mired in stalemate” in its fight against communist forces there. He also suggested that negotiations might prove to be a way out for the United States.

Cronkite’s downbeat characterization was offered at the close of a special report based on the anchorman’s visit to Vietnam during the communists’ Tet offensive, which had begun at the end of January 1968.

“Stalemate,” though, was scarcely an original analysis: It had been invoked for months to characterize the war in Vietnam, as I pointed out in my media-mythbusting book, Getting It Wrong.

What supposedly made it all so exceptional was that Cronkite had turned pessimistic about the war. After all, Cronkite was, as CBS recently recalled, “America’s most trusted newsman” whose assessments supposedly projected unrivaled influence.

Often cited as evidence of such influence is President Lyndon B. Johnson’s purported reaction to Cronkite’s “stalemate” remarks.

As a recent NPR report claimed, “Johnson is said to have told an aide, ‘If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost middle America.'” (The San Francisco Chronicle asserted no such qualification last month in stating, “Johnson remarked to an aide, ‘If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost Middle America.'”)

The president’s presumptive comment has become the stuff of legend, even if versions of what Johnson supposedly said vary markedly.

Mentioned far less often is that Johnson did not see the Cronkite report when it aired, and that there is no clear evidence about whether, or when, he watched the program later, on videotape.

Cronkite in Vietnam, 1968

And mentioned even less often is that the Cronkite report appears to have influenced the president’s public stance on the war not at all.

Indeed, in the days and weeks after the “Cronkite Moment,” Johnson doubled down on his Vietnam policy, urging a renewed commitment to defeating communism in Vietnam.

The president was overtly and vigorously hawkish on the war at a time when Cronkite’s views should have been most potent. But the president in effect brushed aside Cronkite’s pessimism and repeatedly sought to rally popular support for the war effort.

Not only that: the claim that Cronkite was the “most trusted” newsman didn’t prominently emerge until 1972; the term was invoked in newspaper advertising bought by CBS, to tout its coverage of Election Night that year.

Nixon’s “secret plan” for Vietnam is another hoary myth that dates to early 1968 and likewise has proven resistant to debunking. William Safire, a former speechwriter for Nixon and later a New York Times columnist, once wrote of the “secret plan” myth:

“Like the urban myth of crocodiles in the sewers, the [Nixon] non-quotation never seems to go away ….”

Huffington Post invoked the non-quotation in a recent look back at 1968, asserting that “the ultimate winner of the year proved to be a man who campaigned on the thesis that he had a secret plan to end the war in Vietnam.”

No, Nixon did not campaign in 1968 “on the thesis that he had a secret plan,” even though the anecdote does fit the popular image of Nixon as cunning and duplicitous.

As Media Myth Alert has often noted, Nixon never made a “secret plan” a plank of his campaign in 1968. It was a campaign pledge Nixon never made.

His opponents occasionally accused him of having a secret plan for Vietnam, but Nixon pointedly and publicly disavowed the notion.

In an article published March 28, 1968, in the Los Angeles Times, Nixon was quoted as saying he had “no gimmicks or secret plans” for Vietnam.

“If I had any way to end the war,” he was further quoted as saying, “I would pass it on to President Johnson.” (Nixon’s remarks were made shortly before Johnson announced he would not seek reelection.)

That a “secret plan” was not a feature of Nixon’s 1968 campaign becomes clear in reviewing a database of the content of leading U.S. newspapers, including for 1968, the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Baltimore Sun, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, and Chicago Tribune.

The search terms “Nixon” and “secret plan” returned no articles during the period from January 1, 1967, to January 1, 1969, in which Nixon was quoted as saying he had a “secret plan” for Vietnam. (The search period included the months of Nixon’s presidential campaign and its aftermath.)

If Nixon had claimed during the 1968 campaign to possess a “secret plan” for Vietnam, America’s leading newspapers surely would have reported it.

A column that promoted a media-driven trope

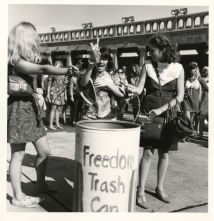

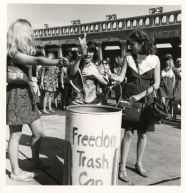

And then there’s the “nuanced myth” of bra-burning, which can be traced to September 7, 1968, and a women’s liberation protest on the boardwalk at Atlantic City, N.J., against the Miss America pageant.

The demonstration’s organizers have insisted that while bras, girdles, high heels, and other items were ceremoniously tossed into a burn barrel dubbed the “Freedom Trash Can,” nothing was set afire. Or as a recent 1968 retrospective in the Orange County Register put it, “the protest occurred flame free.”

But such a statement ignores the accounts of two reporters who were at the protest that day.

One of them, John L. Boucher, wrote the next day in the Press of Atlantic City that as “the bras, girdles, falsies, curlers, and copies of popular women’s magazines burned in the ‘Freedom Trash Can,’ the demonstration reached the pinnacle of ridicule when the participants paraded a small lamb wearing a gold banner worded ‘Miss America.’”

Boucher’s matter-of-fact reference to burning bras appeared in the ninth paragraph of his article, which the Press published beneath the headline:

“Bra-burners blitz boardwalk.”

Boucher’s observation was supported by another reporter at the boardwalk that day, Jon Katz, who in interviews by email and phone, said without hesitation that bras and other items indeed had been set afire during the demonstration.

“I quite clearly remember the ‘Freedom Trash Can,’ and also remember some protestors putting their bras into it along with other articles of clothing, and some Pageant brochures, and setting the can on fire,” Katz said. “I am quite certain of this.”

He also said:

“I recall and remember noting at the time that the fire was small, and quickly was extinguished, and didn’t pose a credible threat to the boardwalk. I noted this as a reporter in case a fire did erupt.”

As I noted in Getting It Wrong, the accounts of Boucher and Katz lend no support for the vivid popular imagery that many bras went set afire in a flamboyant protest on the boardwalk. At most, fire was a modest, fleeting element of the demonstration.

But their accounts make clear that “bra-burning” is an epithet not misapplied to the 1968 protest at Atlantic City.

More from Media Myth Alert:

- After the ‘Cronkite Moment,’ LBJ doubled down on Viet policy

- ‘Mired in stalemate’? How unoriginal of Cronkite

- ‘Lyndon Johnson went berserk’? Not because of Cronkite

- Wasn’t so special: Revisiting the ‘Cronkite Moment,’ 44 years on

- ‘When I lost Cronkite’ — or ‘something to that effect’

- The campaign pledge Nixon never made

- WaPo, Helen Thomas, and Nixon’s ‘secret plan’

- Arrogance: WaPo won’t correct dubious claim about Nixon ‘secret plan’ for Vietnam

- Smug MSNBC guest invokes Nixon’s mythical ‘secret plan’ on Vietnam

- Behind the ‘nuanced myth’: Bra-burning at Atlantic City

- Bra-burning in Toronto: Confirmed

- ‘The Post’: Bad history = bad movie

- Check out The 1995 Blog

- ‘Getting It Wrong’ goes on ‘Q-and-A’